By Marc Blankenship

In the title song of the musical Cabaret, nightclub singer Sally Bowles asks, “What good is sitting at home in your room?” For Sally, it’s no good at all, but for an increasing number of Americans, staying at home is a very attractive option.

According to a new Princeton study, people in all age groups are spending almost two extra hours at home every day compared to 20 years ago. This includes all activities, from work to leisure. While the pandemic accelerated the trend, it has been developing for quite some time.

For anyone selling live events, this may be chilling news. If an industry is built on getting people off the couch for an out of home experience, how is it supposed to survive this cultural shift?

The answer is to adapt to the moment. In the years since lockdowns lifted, the team at AKA NYC has learned volumes about this “new normal” in the world of live experiences. From Broadway shows to cultural institutions to immersive attractions, they’ve gotten people to go to all kinds of places. Here are three of their insights on why audiences leave their living rooms.

“If people are going to get out of the house, it has to feel low risk,” says Kevin Bradley, AKA’s VP, head of arts institutions. “People work from home. They can be entertained at home. If they’re going to leave a place where they already feel comfortable, they have to know it’s going to be worth it.”

In other words, audiences must feel confident they’ll have a good time. “But that message isn’t one-size-fits-all,” Bradley adds. “You have to communicate something that feels authentic to what you’re offering.”

For example, the recent Broadway revival of Enemy of the People initially broke through with audiences because it featured a star performance from Jeremy Strong. However, it wasn’t just his celebrity that made the production feel low risk. Strong is known for thoughtful, complex performances in projects like Succession. He was starring in a play about a fiery social issue. That marriage of performer and material was crucial to the messaging.

“He was familiar to people, and he was familiar to them in this kind of material,” says Marc Jablonski, AKA’s head of business intelligence. “That made it feel more comfortable. If you knew Jeremy Strong, then you knew you could trust him in a show like this.”

Star power isn’t the only way to minimize perceived risk with an out of home experience. “People are drawn to attractions that make them feel something,” Jablonski says. “You can make something feel ‘familiar’ by telling the audience they’re going to feel something meaningful.” He points to an exhibit at Mercer Labs called Dark Matter. This explores how art has embodied the darkest parts of the human psyche.

“Everything about that exhibit said, ‘You will feel something intense,’ and that can be enough to make people visit.”

Another major factor is making an out of home experience feel like an event. “If you can offer a distinct, complete evening, then you’re going to stand out,” says Elizabeth Findlay, AKA’s SVP of client services and media. “People want something they can enjoy with their friends or their family that feels bigger or better than what the couch can provide.”

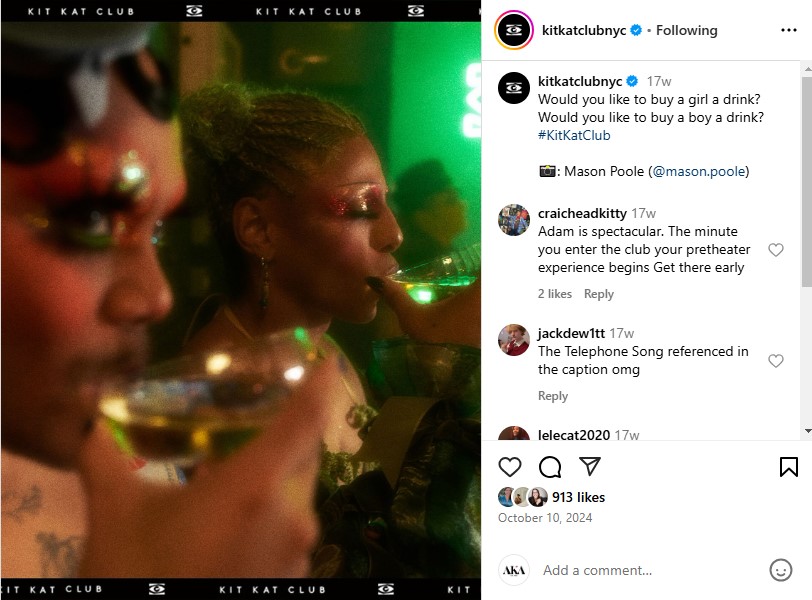

Sometimes, a project becomes an event because it offers a suite of activities. Speaking of Sally Bowles, that’s part of the allure of the current Broadway revival of Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club. Audiences not only see the famous musical but also explore a theater space designed to immerse them in a fully operational nightclub, the Kit Kat Club.

“For a single ticket, that production is giving you everything you want in an evening,” Findlay says. “You get a pre-show with a completely different cast. You get to visit a cool bar; you get to have food. And then you get to see a musical. If you’re commuting, you park once, and then you spend all your time in the same place. It makes it so much easier to plan, and it gives you multiple cool things to do.”

But even if they can’t redesign a performance venue, attractions can still “eventize” themselves.

Bradley says: “I think about how well The Metropolitan Museum of Art has done with its extended hours on Friday and Saturday nights. They’ve been offering that for years, but after the pandemic, those extended hours were re-branded as ‘date nights.’ They offered drink specials, live music, and gallery chats. They encouraged people to post about their date nights on social media. And it’s become far more successful than it was in the previous 15 years.

“It’s the same program, but redefined as something special.”

The last hurdle for homebodies is the fear that the logistics of attending will be too stressful. “It’s a schlep to get somewhere, especially if you’re working from home instead of an office downtown,” says Findlay. “And what if you’ve never been to a particular neighborhood before, or you’ve never been to a particular venue? It can be intimidating.”

That’s where marketers have an opportunity to show compassion. Findlay adds: “Think about how much power there is in pre-event communication. We can say, ‘If you’re traveling by subway, exit from this part of the station. If you’re traveling by car, then this is actually the best parking garage.’ We can assume that people just google everything, but why not save them the effort? Why not give them our insider perspective, so that they know we’re taking care of them?

“You can do the same thing for their experience inside. Take pictures of what the view looks like from every seat in the house or room in the experience, so that before they buy tickets, people understand what they’re going to see. When you’re writing your marketing copy, tell people what the show or experience is about. If you let people know that you really care about their whole experience, from soup to nuts, they’re going to trust you more.”

Trust is essential. If audiences trust that an out of home experience or event will deliver, they’re more likely to recommend it to others. If they learn to trust an entire market sector, then regular attendance might not feel risky.

“I strongly believe that museums aren’t competing with each other, and shows aren’t competing with each other,” Jablonski says. “They’re all part of a larger brand of ‘New York museums, ‘Broadway shows’, or ‘Things to Do’. If we make people feel welcome at one of the experiences offered by the brand, then they’ll feel welcome at all of them. That’s what gets people talking and going out.”